|

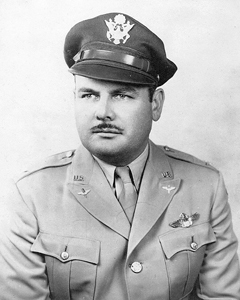

Biography of Colonel Ford J. Lauer

Colonel Ford J. Lauer enlisted in the Air Force in 1925 when

it was a part of the US Army. At that time known as

the Air Service, it was under control of the US Army Signal

Corps. The Air Service was re-designated as the Army Air Corps

in 1926. The Air Corps was small, possessing no more than a few

hundred airplanes and some observation balloons. Rated pilots numbered

less than one thousand, most of them being reservists. Military

aviation at that time was a risky occupation. Airplanes were not

reliable and were commonly referred to as "crates" by the pilots.

They were officially referred to as ships. Radio communication

was in its infancy, and there were no flying aids to speak of.

Cockpit instruments consisted of no more than engine gauges, an

inaccurate compass, and a crude altimeter that was accurate only

to within a hundred feet. Additionally the indicated altitude reading

was always at least thirty seconds old. All airplanes had open

cockpits, and the pilots were exposed to the weather. Thick leather

overcoats had to be worn by the pilots to protect them from extremely

cold temperatures and the constant blast of wind in their faces.

Weather forecasting was primitive and unreliable by today's standards.

Night flying was practiced, but was dreaded by the pilots. Crashes,

or "wrecks" as they were called then, were commonplace. Pilots

who survived their enlistments were lucky. To survive a flying

career was a miracle. Pay for military pilots was about one fourth

that of civilian pilots. As a result most pilots moved on to civilian

jobs after completing their initial military obligation. This left

a small core group of career pilots who throughout the 1920s and

1930s, transformed the Air Corps from an observation and support

arm into one with offensive capabilities. Lauer was a member of

this core group. Other members included Henry Arnold, Ira Eaker,

Carl Spatz, Frank Andrews, Curtis LeMay, Nathan Twinning, Caleb

Haynes, Robert Olds, Torgiles Wold, Robert Peaslee, D.H. Alkire,

and Ralph Koon. Some of these names later became well known, while

others remained obscure. All of these men together became the "Fathers" of

modern military aviation.

Though he possessed only a high

school education, Lauer was an extremely intelligent individual.

He was born August 18, 1905 at Wawaka, (Noble County),

Indiana. He was the son of a farmer. Being

mechanically inclined, Lauer built a motorized bicycle as a

boy. Also very athletic, Lauer was captain of his high

school basketball team. He graduated from Wawaka High School

in 1923 with very high marks. After driving a truck for

a year, Lauer decided he wanted to do something else with

his life. He had heard of the exploits of World War I pilots,

and had seen the "Barn Stormers" of

the day displaying their feats. With his father's consent, Lauer

enlisted in the Air Service. Early in his flying career, Lauer

established himself as a very talented pilot. Despite being burned

in a fiery crash during flying school, he resumed training.

After

completing flying school, Lauer was stationed at Mitchell Field

on Long Island, New York. Long Island was by all accounts "The Cradle of Aviation." The Grumman,

Republic, Vought, and Curtiss companies among others were located

on Long Island. The pilots stationed at Long Island therefore took

advantage of the opportunity to fly the latest airplane designs

that rolled out of the factories. Lauer quickly gained a reputation

as a natural stick and rudder man, and was referred to by several

persons who served with him as "one of the most superb pilots" they

ever knew. Throughout the late 1920's and into the 1930's,

aviation records were being set and broken weekly. New

airplane designs were being introduced at a rapid pace.

For the pilots of this era, flying was extremely exciting

but also hazardous. The only way to test new airplane designs

was to fly them. Many of the pilots were maimed or killed

in crashes.

Lauer became one of the original four engine

pilots of the Air Corps. He was a member of the famous

2nd Bomb

Group at Langley Field during the late 1930's. The 2nd was

selected to receive the first thirteen Boeing B-17 bombers

in 1937. With the B-17, the men of the 2nd developed

long range precision navigation. They also developed the

concept and methods of flying long distances in formation

to bomb specific targets, thus giving the military a new

offensive air arm. Many of the methods they developed are

still used in today's modern Air Force. In addition to the

difficulties of developing this new air arm, the men of the

2nd also had to fight a daily battle just to

ensure its continuation. The Navy's battleship admirals protested

strongly to the US Congress that the Air Corps was encroaching

in their area. At this time the US was an isolationist nation,

which saw no need for offensive weapons. The B-17 project

had been approved by congress as a coastal defense weapon.

The battleship admirals reasoned that the Navy was solely

responsible for coastal defense. As if attacks by the battleship

admirals weren't enough, the B-17 project was also attacked

by the Army's infantry generals. Being a part of the Army,

the Air Corps was subordinate to those generals, none of

whom were pilots. The generals insisted that the Air Corps

mission was to support the infantry. They refused to consider

the airplane's value as an independent weapon. In the end,

the B-17 project was saved by a handful of farsighted US

Congressmen who were uncomfortable with events happening

in Germany and Japan.

As the United States prepared for and

entered World War II, the men of the 2nd Bomb

Group at Langley were siphoned off to form new bomb groups.

As soon as the new groups were established and the expertise

passed on, the process started again. In this way, Lauer

established the 34th Bomb

Group in May of 1941, the 303rd Bomb Group

in February of 1942, the 15th Bomb Wing in

June of 1942, and the 304th Bomb Group in

September of 1942. Organizing and training new groups

was accomplished at a frantic pace, and severely tested

the metal of the commanders. These were men who had been

accustomed to functioning in a peacetime environment

with well-trained pilots. The urgency of World War II

necessitated throwing young men with minimal flight training

into combat. To make matters worse, equipment, supplies,

and especially airplanes were in short supply. While

in command of the 304th Bomb Group, Lauer

became aware that the 2nd at Langley was scheduled

for deactivation. Lauer succeeded in having the 304th trade

designations with the 2nd in November of 1942.

The 2nd was

the oldest group in the Air Corps, dating back to World

War I, and Lauer desired to have its name and traditions

live on. The 2nd lives on to this day, flying

B-52's, and they owe their existence to Lauer's resourcefulness.

Beginning immediately after the Japanese bombing of Pearl

Harbor, the 34th Bomb Group, with Lauer as its commander, flew patrol and antisubmarine missions

off the coasts of the United States. As commander of

the 15th Bomb

Wing, Lauer participated in the bombing of Dutch Harbor,

Alaska in the summer of 1942. The Japanese had invaded

and occupied Alaskan soil primarily as a diversion

for their invasion of Midway Island.

After completing

the group's training, Lauer took the 2nd (former

304th) Bomb Group

overseas in March of 1943. Soon after arrival however, he

was transferred to Headquarters, North African Theater

of Operations. His exact duties are unknown. He served

in this capacity until being placed in command of the

99th Bomb Group, 15th Air

Force. The 99th flew B-17s out of Tortorella,

Italy. Prior to Lauer taking command, the 99th primarily

bombed bridges and railroads in northern Italy. Under Lauer,

the 99th was

tasked with taking the war into the heart of southern Germany

and the occupied countries to the south and east. The German

air forces fought fiercely to defend their home skies. With

every mission the bombers flew the gauntlet of enemy fighters

and flak. Enemy fighters concentrated their attacks on the

group leaders in an effort to shoot them down and break up

the formations. Lauer forced the 99th to tighten

and improve their flying formations, which resulted in higher

concentrations of bombs on target.

On February 25, 1944,

Lauer led the 99th into what became one of the bloodiest air

battles of the war. The target was Regansburg, Germany. The

group was attacked by an estimated eighty German fighters,

and there were no allied fighters to provide protection.

The fighters intercepted the group after it crossed the Alps,

and stayed with it to the target and all the way back to

the Alps. If not for Lauer's expertise and resourcefulness

in holding the formation together, the entire group would

have been scattered and annihilated. Lauer was awarded the

Silver Star for this mission. Lauer was also awarded the

Distinguished Flying Cross for leading a mission on April

23, 1944. The target that day was the Weiner Neustadt aircraft

factory in Austria. Despite his airplane being severely damaged,

he held the 99th together for

a successful bombing. In June of 1944 he commanded the

first shuttle bombing mission into Russia. Being able to

continue on and land in Russia made it possible to bomb targets

that were otherwise unreachable. Lauer was awarded the Legion

of Merit for this mission. After twenty-one months in the

European Theater, Lauer was transferred back to the US.

In

January of 1945, Lauer was placed in command of the Consolidated

B-32 "Dominator" bomber

development project. His duties involved flight evaluation

of the 140,000-pound bomber. The B-32 project served as backup

to the Boeing B-29 project, in case it failed. As it turned

out the B-29 was highly successful, and the B-32 project

was soon cancelled.

After World War II ended, Lauer was placed

in command of Johnson air base in Japan as part of the

occupation force. After returning to the United States in 1947,

Lauer commanded several airbases. He retired from the newly created

United States Air Force in 1949.

Lauer made many friends

during his career and earned the respect of his peers. Men

who served with and under him have stated that he was a compassionate

leader. He was known as a "Soldier's Colonel." They have

also stated that he was a perfectionist when it came to flying.

Several have attributed their surviving World War II to him.

Upon his retirement in 1949, Lauer had accumulated over 8000

hours of flying time in over 100 types of airplanes. Though

8000 hours today is common, it was an unheard of total for

the time period of Lauer's career. 600 of those flying hours

were in combat, in both the European and Pacific theaters.

Lauer passed away in 1964, and was buried at the Fort Sam

Houston National Cemetery, San Antonio, Texas.

Written by Ford J. Lauer III |